Today, GPS technology is so closely integrated with our daily lives that it’s hard to imagine a world without it. One of the main inventors who made a significant contribution to the development of GPS was a graduate of Bronx High School, Ivan Getting. We’ll tell you how it all happened and what made this American scientist with a not-so-American name famous on bronx-future.com.

A Major Discovery

After the first satellite was launched, researchers worldwide meticulously studied its operation. The radio signals, which changed frequency depending on the satellite’s movement, caught the attention of scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. They noticed the Doppler effect—a phenomenon in which a signal’s frequency changes as its source moves relative to the observer. This observation became the basis for the idea that a satellite’s location could be determined from Earth, and vice versa—the location of a ground-based object could be determined using satellites.

In 1958, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) began developing the Transit system, the world’s first satellite navigation system, which provided precise positioning for the military, including submarines, starting in 1960. By 1968, the system consisted of 36 satellites and provided accuracy within tens of meters. It operated until 1996 when it was replaced by GPS.

The idea for a more advanced navigation system came from the founding president of the Aerospace Corporation, Ivan Getting, whom we’ll discuss a bit later. In 1963, a satellite navigation model based on signals from four satellites was proposed as part of the 621-B study. This allowed for the use of less expensive, highly accurate clocks in the receivers. The decision to place accurate clocks on the satellites themselves paved the way for the miniaturization of receivers, which eventually made it possible to embed GPS in phones.

The successful development of GPS was also aided by other innovative technologies, including the emergence of microprocessors, new computers, and atomic clocks. The Timation program, launched at the Naval Research Laboratory, tested the first satellites with precise timing. The culmination was the launch of a satellite with an atomic clock in 1974.

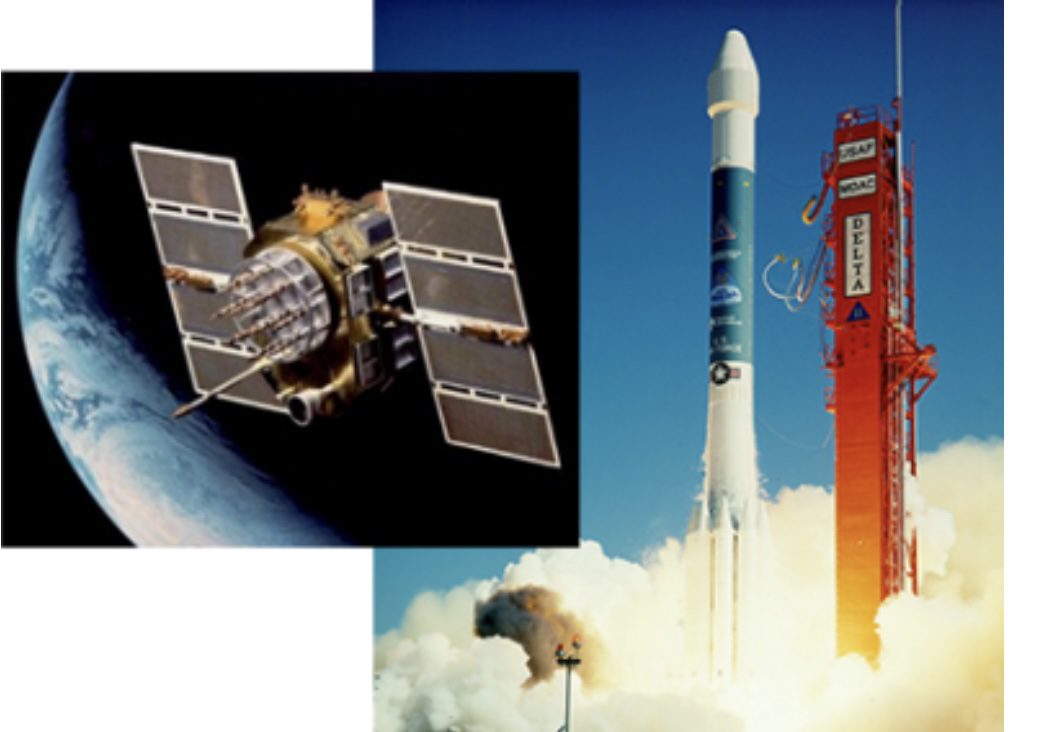

In 1972, under the leadership of Colonel Bradford Parkinson, a merger of Transit, Timation, and 621-B into a single system was initiated. In 1973, the new project was given the green light by the U.S. Department of Defense. Since then, the development of Navstar satellites has been underway.

The first of them were launched in 1978, and by the 1980s, the system was being actively tested.

In 1983, President Reagan authorized the use of GPS for civil aviation. Since then, commercial access to GPS has been expanding. In 1989, the first portable GPS device for the mass market appeared. At the same time, fearing that the system could be used by U.S. adversaries, the Department of Defense limited the signal’s accuracy for civilian use through a mechanism called “selective availability.”

Integrating GPS into Everyday Life

The technology became increasingly integrated into everyday life. In 1999, the first mobile phone with built-in GPS was released—the Benefon Esc!—which marked the beginning of the mass adoption of navigation in mobile devices and cars.

In 2000, the U.S. government lifted the accuracy restrictions for civilian users (the so-called “selective availability”), which increased the accuracy of GPS for ordinary citizens tenfold literally overnight. Thanks to the rapid drop in the price of GPS receivers (from $3,000 to $1.50) and the increase in accuracy, GPS began to rapidly penetrate transportation, logistics, household devices, shipping, and other industries.

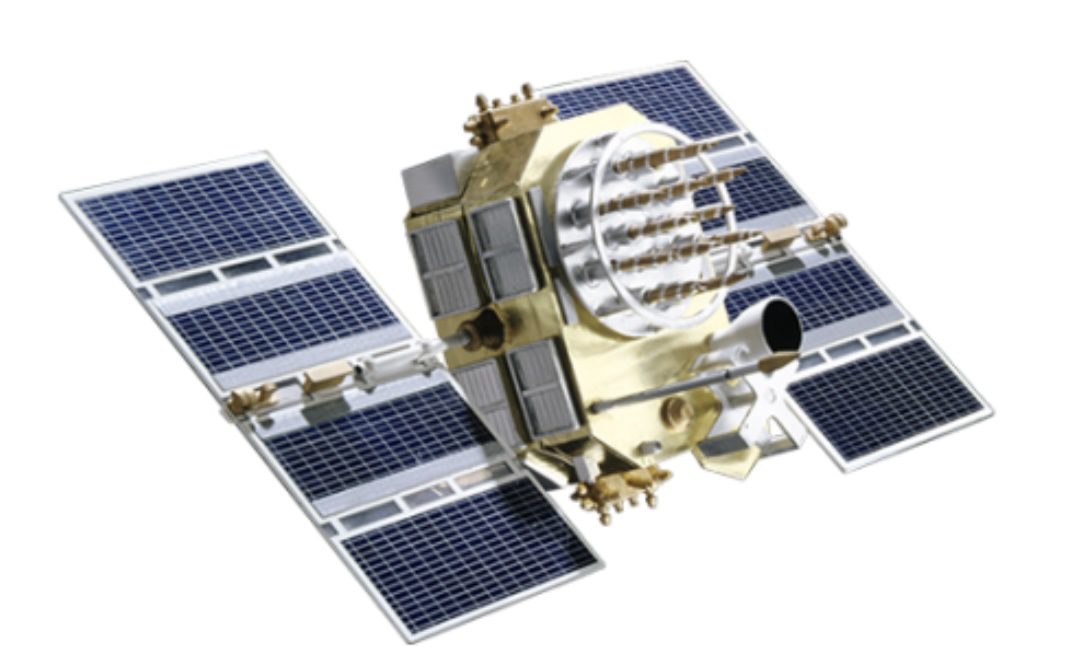

Given the growing needs of both the civilian and military sectors, a system modernization began. By 2005, several generations of satellites were already in operation (II, IIA, IIR), and new modernized IIR-M and IIF satellites were gradually launched until 2017. In parallel, the GPS III program—a generation of satellites with expanded capabilities—was launched. The first GPS III satellites were launched between 2018 and 2020. Research and development in this area are constantly ongoing, and technologies are being improved and developed.

GPS has impacted more than just navigation—its data is integrated with cartography, meteorology, and data synchronization, and is also used in financial systems, telecommunications, science, construction, and agriculture. Since the early 1980s, GPS has contributed about $1.4 trillion to the U.S. economy. For example, from 2007 to 2017, navigation applications helped Americans save 52 billion gallons of fuel and avoid over a trillion miles of wasted trips.

Bronx’s Ivan Getting: A Key Figure

The founding president of the Aerospace Corporation, Ivan Getting, played a key role in the creation of the Navstar satellite navigation system.

The beginning of this story dates back to the 1940s, when Getting, working at MIT’s Radiation Laboratory, was developing radar-based weapon control. Meanwhile, in a neighboring laboratory, the ground-based Loran navigation system was being created, whose ideas later inspired Getting. In the 1950s, already heading the scientific and technical department at Raytheon, he worked on the Mosaic project—a missile guidance system that was supposed to work similarly to Loran, but using satellites instead of ground-based transmitters. Getting realized that if enough satellites were launched into space, it would be possible to provide precise three-dimensional positioning anywhere on the planet. This is how the Navstar concept was born.

In 1960, when the U.S. Air Force tasked him with creating a new nonprofit research organization—the Aerospace Corp.—he immediately initiated a study of the idea of global satellite navigation. Despite being busy with other important projects, satellite navigation remained Ivan’s main passion. However, its implementation required huge funds—at least 18 satellites and billions of dollars. Getting actively promoted his project, reaching out to high-ranking officials, advisers, and military personnel.

“I was peddling it everywhere, advertising, advertising,” Getting recalled.

Initially, few people believed him, but later the Pentagon agreed to finance demonstration tests, and then the full-scale development of the system.

The first Navstar satellite was launched in 1978, and by 1985, the system was already able to work in two coordinates in most regions.

The Engineer’s Calling

Despite the fact that Ivan Getting’s parents were far from science (his father was involved in Slovak politics and publishing, and his mother was a homemaker), the boy’s interest in technology showed up early. Military engineering was not an obvious choice for him: as a child, he didn’t dream of tanks or planes. But after being introduced to the Meccano construction set, Ivan became fascinated with technology, learned to understand mechanics, and later enrolled at MIT, where he received a scholarship as a winner of the Edison contest. After graduating in 1933, unable to find a job in his field, Getting earned a degree in astrophysics from Oxford and then studied nuclear physics at Harvard, where he created the first high-speed trigger.

Ivan Getting did not plan a military career, but, as he himself said, “the war sucked him in.” During World War II, he joined the Radiation Laboratory at MIT. After the Korean War began, the U.S. Air Force invited Getting to serve as an adviser. For his work, Getting received the Medal for Merit from President Truman in 1948—one of the highest awards for scientists at the time.

Despite his exceptional achievements, Ivan did not hide his mistakes. In one instance, while trying to replicate a nuclear fission experiment, he used an old boron-glass hood that absorbed neutrons, causing the experiment to fail. In another, a balloon experiment ended in an explosion and burns. And while working at Raytheon, production was stopped due to a cable mismatch that cost the company $300,000—Getting kept the cable as a reminder of the importance of paying attention to the details.

Over time, Getting moved from engineering to management. At Raytheon, he initiated the construction of modern offices with landscaping and private offices, adopting the experience of Bell Labs, unlike the cramped industrial spaces common at the time.

“I was an engineer myself,” Getting said. “I didn’t want to be one of a thousand. I wanted individuality. Scientists and engineers, if they’re any good at all, want individuality; they want to be able to meet with other engineers, but they don’t want to be herded like sheep. And the cost of proper office space is the smallest part of the total cost of running a high-tech company.”

Getting believed that engineers should be given not only comfort but also recognition. Although public fame was limited in the military field, he still tried to motivate people personally, supported young specialists, and encouraged their initiative. Colleagues recalled that his leadership style—sincere and inspired—gave people confidence and helped them unlock their potential.